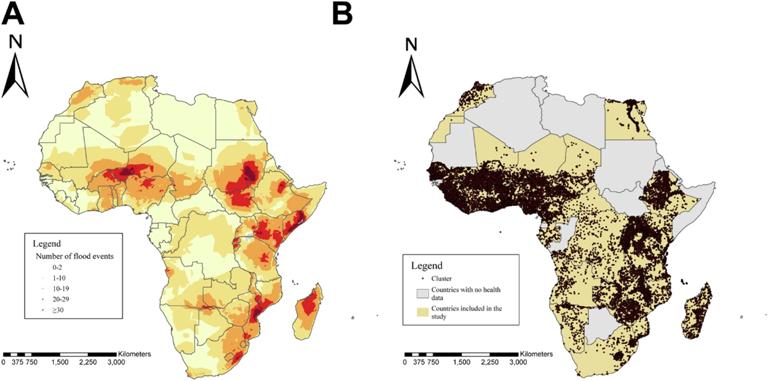

Floods are becoming more frequent and severe in the context of climate change, with major impacts on human health. However, their effect on infant mortality remains unknown, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. We conducted a sibling-matched case-control study using individual-level data from Demographic and Health Surveys in Africa during 1990–2020. Individual flood experience was determined by matching the residential coordinates with flood events from the Dartmouth Flood Observatory database. Using data from 514,760 newborns, we found increased risks of infant mortality associated with flood exposure across multiple periods, with the risks remaining elevated for up to four years after the flood event. Overall, flood exposure was associated with 3.42 infant deaths per 1000 births in Africa from 2000 to 2020, approximately 1.7 times the burden associated with life-period exposure. This multi-country study in Africa provides novel evidence that flood events may increase infant mortality risk and burden, even over years after exposure.

This study has several notable implications. First, as a quintessential acute climate phenomenon, flood could have a long-lasting impact on human well-being that has been overlooked for decades. Policymakers should prioritize comprehensive, long-term disaster preparedness and resilience. Establishing sustained disaster recovery services, including rebuilding efforts and health assistance, is crucial for helping households recover, providing secure shelter for children, and mitigating the long-term health risks associated with flood events. Second, this study identified several flood-vulnerable regions in Africa and reported an increasing burden of infant mortality associated with flood events in recent years. The heightened frequency and severity of floods underscore the importance of implementing effective mitigation and adaptation strategies for flood events. For example, it is imperative to establish flood forecasting systems with high temporal and spatial resolutions in flood-prone regions to enhance preparedness and response capabilities. Third, given the vulnerability associated with low education levels, flood-fragile housing materials, and inadequate sanitation facilities, local governments should provide resources to promote awareness of post-disaster child healthcare and disease prevention for vulnerable women in affected communities. Climate adaptation measures, including improvements to infrastructure, land use planning and medical resource allocation, are crucial in climate-sensitive regions in response to the escalating frequency and severity of flood events in the context of climate change.

This study also has several limitations. First, they only utilized the DHS (Demographic and Health Survey) dataset collected in African countries, so generalizability of the findings to other regions of the world was restricted. Second, the small sample size for matched flood events and infant deaths prevented us from estimating country-specific ORs, so they had to use uniform ORs across different countries in estimating the infant mortality burden, which may introduce some degree of uncertainty. Third, disaster reporting has improved significantly in recent years due to advancements in communication technology. Therefore, floods from earlier years were more likely to be underreported. The increased burden of infant deaths related to floods may be partly associated with the rise in flood reporting rate, potentially leading to an underestimation of the associated with mortality burden in earlier years. Forth, there is a potential gap between multiple births for a mother, despite the fact that they compared flood exposures within the same mother, there are still some individual-level factors that could have changed between births. Fifth, this study only included deceased infants with surviving siblings, which may lead to an overestimation the risk and burden of infant death associated with floods. This is because infants with siblings may receive fewer resources from their families and face higher mortality risks from flood exposure compared to those without siblings. Finally, due to the inaccessibility of data on the governmental specific response to floods, they could not include mitigations or adaptations as covariates or possible modifiers in the statistical analyses.

In conclusion, this present study in 37 African countries provides novel and compelling evidence that flood events may increase infant mortality risks over the short and long terms. For the first time, they quantified the infant mortality burden associated with flood events, which had increased in Africa from 2000 to 2020 and was disproportionately distributed. Their findings emphasize the necessity of developing sustainable intervention and adaptation strategies to continuously support affected women and children in the aftermath of floods, especially for susceptible subpopulations and regions.

Sources:

Nature communications

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-54561-y#Sec6 .

Provided by the IKCEST Disaster Risk Reduction Knowledge Service System

Comment list ( 0 )