The frequency at which extreme fires occur around the world has more than doubled during the past two decades, according to an analysis of satellite data. The trend is driven by the exponential growth of extreme fires across vast portions of Canada, the western United States and Russia, researchers say.

The results provide the first solid evidence to support a nagging suspicion that many scientists and others have had as they watch a seemingly endless series of cataclysmic infernos scorch ecosystems and communities: wildfires have increased somehow, and climate change is almost certainly a factor.

“It’s the extreme events that we care about the most, and those are the ones that are increasing quite significantly,” says lead author Calum Cunningham, an ecologist at the University of Tasmania in Hobart, Australia. “Surprisingly, this has never been shown at a global scale.”

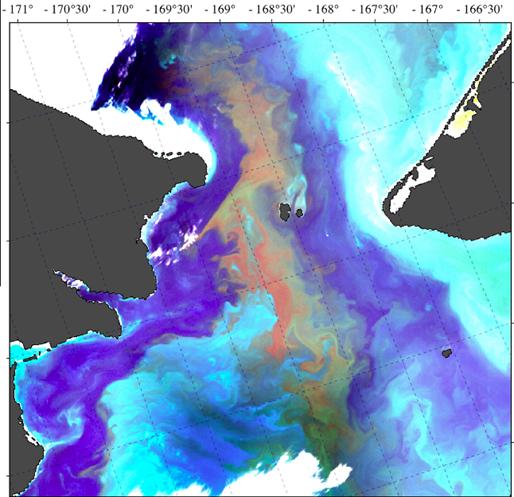

In July 2022, Evie Fachon was aboard the research vessel Norseman II searching for tiny but dangerous creatures lurking off the Alaskan coast. As the vessel approached the Bering Strait, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) Ph.D. student watched as counts of the single-celled organism Alexandrium catenella ticked up in images of water samples. By the end of the cruise, the team detected the largest toxic bloom of A. catenella ever seen in polar waters, stretching at least 600 kilometers and triggering risk advisories about potentially unsafe marine harvests.

Scientists say these polar blooms are more likely to occur as climate change pushes the oceans to ever higher temperatures. “The warmer it is, the faster [the cells] can potentially grow and multiply,” says Fachon, lead author of a paper describing the 2022 bloom. The work, published last week in Limnology and Oceanography Letters, found algal concentrations that were more than 100 times higher than the level needed to trigger public health warnings.

A.Catenella blooms are a problem that’s long plagued fisheries at lower latitudes, including southeastern Alaska. But in recent years, scientists have found evidence the blooms are becoming a threat to Arctic communities as well. During previous research cruises, Fachon’s Ph.D. adviser, WHOI’s Donald Anderson, sampled seafloor sediments and documented “massive” beds of A. catenella cysts, a dormant form of its life cycle, stretching more than 1000 kilometers from the Bering Strait to the western edge of the Beaufort Sea. When the conditions are right, these cysts can seed harmful blooms in surface waters.

Fachon and colleagues suspect the 2022 bloom germinated somewhere in the Bering Sea, possibly in Russia’s Gulf of Anadyr. As strong winds pushed nutrient-rich western Bering Sea water into warmer Alaskan waters, favorable temperature and nutrient conditions allowed the algae to expand.

The unprecedented polar bloom represents an evolving public health threat, says Christopher Gobler, an ecologist at Stony Brook University who published a 2017 study showing ocean warming has expanded the range of harmful algal blooms poleward in the North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans. “It’s really something that can take the regulatory agencies—and, even in some cases, the medical community—by surprise because everything is put in place to deal with the known, not the unknowns.”

Unlike many coastal areas in the United States, which monitor ocean samples for A. catenella, Bering Strait communities lack infrastructure to detect blooms like the 2022 one. Local health officials only sprung into action to distribute advisories to the surrounding tribes, which rely on subsistence harvesting, after the researchers shared their high counts of A. catenella.

Gay Sheffield, a marine mammal biologist with MAP and co-author of the new study, says she thinks it might be luck that no one was killed. That August, a family harvested a clam north of Savoonga, a community on St. Lawrence Island. Because of a recent advisory, they sent the clam in for testing instead of eating it—and its toxin load was more than five times the food safety limit.

Research cruises don’t happen every summer. So Sheffield has been working with another study author—Emma Pate, an environmental planner with the Norton Sound Health Corporation—to build better capacity for sampling water when local algae conditions may be dangerous and to secure funding to build a testing lab in Nome.

But monitoring water across such a vast area is tricky when gaps in knowledge still exist about how the blooms behave and why some are especially toxic. Fachon’s work showed the 2022 bloom was far more toxic than any recorded in the Gulf of Maine, which has long been monitored.

Researchers are still trying to understand how the toxins move through the food web as well. Elsewhere in the world, bloom-related warnings have mainly focused on clams and mussels, which are known to accumulate poisonous loads of toxins. But the tribes in the Bering Strait region also rely on seabirds, seals, walruses, and whales.

Pate and Sheffield have been sending samples of locally harvested animals to a state lab for testing. It’s not a task they take lightly; asking for samples is like taking food directly off dinner plates, Pate notes. But since the 2022 bloom, residents are becoming more familiar with precautions and the need for testing. “It’s a learning process, because we still need more data,” Pate says.

Sources:

NATURE

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-02071-8 .

Provided by the IKCEST Disaster Risk Reduction Knowledge Service System

Comment list ( 0 )